Scooping a handful of wool, you feel the coarse fibers cling to your palms, thick with the scent of lanolin and earth. Somewhere, in the cool shade of an earthen courtyard, a Moroccan Berber woman kneels beside a heap of fleece, her hands moving with practiced precision. She is not merely cleaning wool; she is reviving something ancient, something that will, in time, warm a child’s shoulders or soften the floor of a stone-built home. In her world, craftsmanship is not an act of creation but an extension of life itself. It is woven into the cadence of daily rituals, where the hum of a loom or the steady rhythm of a millstone is as natural as breath.

1. A Moroccan Berber Woman’s Ritual of Cleansing Wool

The process begins with hands, always hands. Roughened by time yet deft as river reeds, they plunge into vats of water drawn from the communal well, lifting sodden tufts of sheep’s wool into the open air. The Moroccan Berber woman knows wool must be purified, stripped of dust and lingering traces of the animal’s life before it can be reborn as a thing of beauty. She works under the sun, kneeling beside her task, watching the dirt cloud the water before it settles, as if the past is being rinsed away.

In the High Atlas, the cleansing of wool is not a chore but a gathering. Women sit in clusters, laughing, exchanging news, their voices rising like birds startled from the olive trees. Their grandmothers did this, and their granddaughters will too. It is an unbroken thread, one that stretches across time, linking past and present with the simplest of gestures—a hand wringing out wool, a sigh escaping as the day’s work unfurls before them.

The scent of fresh wool lingers long after the fibers are stretched across low stone walls to dry. It carries the promise of warmth, of blankets woven on looms tucked into corners of family homes. Each thread, each strand, holds the weight of history, softened by hands that know the rhythm of craft like they know the rhythm of their own heartbeats.

2. Weaving: How a Moroccan Berber Woman Tells Stories in Thread

The loom is a fixture in a Berber household, its wooden frame resting against mud-brick walls, waiting. When the time comes, the Moroccan Berber woman settles before it, her fingers finding the taut lines of warp threads, plucking them as a musician might a harp. The process is meditative, a dance between hand and fiber, between memory and design.

Patterns emerge like whispered stories. The red of pomegranate skins, the deep indigo of desert twilight, the saffron glow of a midday sun—these are not mere colors but echoes of the land, infused into the wool with natural dyes prepared from crushed roots and dried petals. The motifs tell of mountains and rivers, of fertility and protection, of ancestors whose footsteps still seem to linger in the high passes of the Atlas.

For a Moroccan Berber woman, weaving is not simply about utility; it is an act of preservation. A rug is not just a rug, but a history unfurled across its surface. When she beats the weft into place, she is not merely securing wool against wood; she is securing lineage, language, a way of seeing the world that refuses to fade, even as the modern world encroaches upon her village’s edges.

3. The Timeless Churning of Milk by a Moroccan Berber Woman

Each morning, before the village stirs, she ties the goat-skin bag to a wooden beam, filling it with fresh milk drawn before dawn’s light seeps through the sky. With steady, deliberate motions, she swings it back and forth, a motion as old as the mountains themselves. The milk thickens, curdles, transforms into butter and buttermilk, a quiet alchemy that has nourished generations.

The bag, sewn by hand from a single tanned hide, carries the scent of the herd, of warm fields and grazing animals. It is never merely an object—it is a companion of labor, softened by time, darkened by use. Her grandmother’s hands once tied similar knots; her mother once counted the swings, waiting for the subtle change in texture that signals readiness.

Churning milk this way is not about efficiency. It is about patience, about honoring a process that cannot be rushed. The woman hums as she works, the melody rising and falling with the rhythm of the swinging bag. The song is older than she is, perhaps older than the village itself. When the butter finally emerges, golden and cool beneath her fingers, she does not celebrate. She simply moves to the next task, as her ancestors did before her.

4. Grinding Wheat: A Berber Woman’s Bond with the Millstone

The stone is smooth beneath her hands, worn down by centuries of touch. Each morning, she kneels before the millstone, placing a handful of wheat into the hollowed surface. With slow, deliberate movements, she turns the upper stone against the lower, the grain crushed into flour beneath the ancient weight of tradition.

This is the sound of sustenance, the gentle scrape of stone against stone, the whisper of wheat surrendering to something greater. The Moroccan Berber woman knows the rhythm instinctively, as if it has been etched into her bones. It is a ritual of patience, of effort, of quiet communion with the tools that have shaped her people’s survival.

The flour will become bread, and the bread will be shared—torn by hand, dipped into argan oil, offered without pretense. There is an honesty to this act, to the way a single stone holds the weight of history, to the way her hands coax life from something so simple. Here, in the hush of dawn, she is not just grinding wheat. She is turning the wheel of time itself.

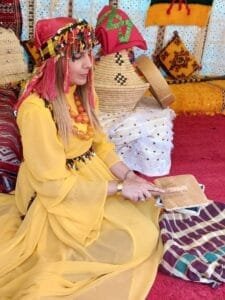

5. How a Berber Woman Wears and Cooks with Handicrafts

The garments she wears are not factory-made. They carry the scent of wool dyed in vats of boiling water, the faint memory of nimble fingers stitching each seam. The Moroccan Berber woman dresses in woven shawls, in tunics spun from the very fleece she once washed in a mountain stream. Each piece is a testament to skill, to the enduring patience of those who shape thread into something that embraces the body.

And then there is the kitchen, the hearth where another kind of craft unfolds. She lifts a clay pot, its surface darkened by years of slow cooking, its curves shaped by hands that molded it from riverbed earth. She does not question its imperfections; she welcomes them. A tagine simmers over embers, steam curling like incense into the morning air. The scent of saffron and cumin, of coriander crushed between calloused fingers, fills the space.

Everywhere she turns, something handmade surrounds her. Not as an aesthetic choice, but as a way of life. The cloth she wears, the pot she stirs, the bread she breaks—each is a quiet homage to the artisans who came before her. To a lineage of makers who, without fanfare, wove beauty into the everyday.